Infection with Zika virus during pregnancy can result in serious neurological disorders, fetal abnormalities, and even fetal death. Until recently, scientists have not fully understood how this virus manages to cross the placenta—a vital organ that nurtures a developing fetus while forming robust barriers against harmful microbes and chemicals.

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, along with collaborators from Pennsylvania State University, have published their findings in Nature Communications regarding the strategy Zika employs for covertly spreading within placental cells. Their discovery could help prevent or control this devastating condition that began as an epidemic in the Americas starting in 2015 and affected millions by 2018.

“Understanding how Zika virus spreads through the human placenta to reach the fetus is critical,” said Dr. Indira Mysorekar, a co-senior author at Baylor College of Medicine, E.I. Wagner Endowed Professor in Internal Medicine II, chief of basic and translational research, and professor of medicine – infectious diseases.

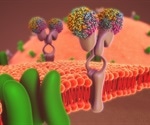

The researchers found that Zika virus constructs intricate underground tunnels—tiny tubes known as tunneling nanotubes—that enable the transfer of viral particles to neighboring cells not yet infected. “We discovered that these tiny tunnel formations are solely driven by a protein called NS1 from the Zika virus,” explained Dr. Rafael T. Michita, postdoctoral research associate in Mysorekar’s lab and first author on this study.

“Exposure of placental cells to the NS1 protein triggers tunnel formation,” he continued. “As these tunnels expand and connect neighboring cells, they create an opportunity for the virus to invade new cells.” It is worth noting that Zika stands out among its viral family members, including dengue and West Nile viruses, as it’s one of only a few that can trigger such tiny tunnel formations in multiple cell types.

Other unrelated viruses like HIV, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), influenza A, and SARS-CoV-2 also form these tunnels to spread from infected cells to uninfected ones. However, this is the first time that Zika infection has been shown to create tunneling in placental cells.

The tiny conduits are not limited to viral particles; they can transport RNA, proteins, and mitochondria—the primary source of energy for a cell—from an infected cell to its neighbors. “We propose that moving mitochondria through these tunnels may provide additional energy support to virus-infected cells, thereby promoting the virus’ replication,” stated co-author Long B. Tran, who is a graduate student in Mysorekar’s lab.

The researchers also noted that traveling through these tiny tunnels can help Zika avoid triggering large-scale antiviral responses from placenta defenses like interferon lambda (IFN-lambda). “Mutant strains of Zika virus that do not form these tunnels induce robust IFN-lambda responses, which could limit the spread of infection,” Michita said.

Overall, this study reveals a sophisticated strategy used by Zika to covertly infect placental cells while utilizing mitochondria for propagation and survival. Moreover, it shields the virus from immune system detection. “These findings offer crucial insights that could be utilized to develop targeted therapeutic strategies against this stealth transmission mode,” Mysorekar concluded.

Key members of the research team included Steven J. Bark and Deepak Kumar from Baylor College of Medicine, along with Shay A. Toner, Joyce Jose, and co-senior author Anoop Narayanan from Pennsylvania State University. This work was supported by grants from NIH/NIAID (R01AI176505), NIH/NICHD (R01HD091218) and startup funds from Penn State. The project also received support from the Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core at Baylor College of Medicine, funded by CPRIT Core Facility Support Award CPRIT-RP180672 and the NIH grants CA125123 and RR024574.